The process of claim construction—interpreting the meaning of the words used in a patent claim—can be confusing at the best of times. At its worst, as in the Federal Circuit’s Dupont v. Unifrax decision this week, it most closely resembles an exchange from Lewis Carroll’s “Through the Looking Glass.”

“I don’t know what you mean by ‘glory’,” Alice said.

Humpty Dumpty smiled contemptuously. “Of course you don’t—till I tell you. I meant ‘there’s a nice knock-down argument for you !’”

“But ‘glory’ doesn’t mean ‘a nice knock-down argument,’” Alice objected.

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.”

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master — that’s all.”

In Unifrax, the Federal CircuitSee CAFC showed a determination to be the master of the meaning of words—even if it requires them to make interpretations as counter-intuitive as Humpty Dumpty’s take on ‘glory.’

When 100% Isn’t 100%

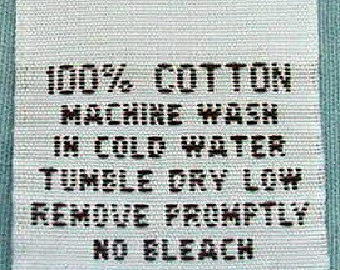

Everyone is familiar with what “100%” means. It’s on juice boxes, telling us that the product is nothing but juice. It’s on clothing, telling us that our shirt is made of nothing but cotton. We even have a shorthand emoji for it—💯.

We use “100%” whenever we understand that something is composed entirely of one thing, with nothing else.

But according to the Federal CircuitSee CAFC, the meaning of 100% is something totally different.

Dupont v. Unifrax

Dupont owns a patent on a type of laminated flame barrier, used to protect aircraft fuselages from fires. Dupont’s patent specifically states that it covers a multilayer laminate. In addition to a film layer and an adhesive layer, neither of which is at issue here, the laminate also includes:

(iii) an inorganic refractory layer; wherein the inorganic refractory layer of (iii) comprises platelets in an amount of 100% by weight with a dry areal weight of 15 to 50 gsm…

U.S. Pat. No. 8,607,926 (emphasis added).

100% by weight is fairly clear. 100% of the layer, when dry, must be platelets (and must weigh from 15-50 gsm). But that language isn’t clear-cut if you’re the Federal CircuitSee CAFC. According to two CAFC judges[1. Judge O’Malley dissented, believing that the limitation was quite clear in meaning exactly what it says—100% by weight.], instead of the plain meaning of “100% by weight”, what the patentee actually meant by this was “[t]here is no carrier material such as resin, adhesive, cloth, or paper in addition to the inorganic platelets. There may be some residual dispersant arising from incomplete drying of the platelet dispersion.” They did this based on various brief passages in the specificationThe section of a patent that provides a description of the invention and the manner and process of making and using it. It must enable the "person having ordinary skill in the art" to reproduce and use the invention without undue experimentation. A patent's claims are interpreted in light of the specification. which mention other embodiments that aren’t 100% platelets by weight and a related patent, but ignore portions of the specificationThe section of a patent that provides a description of the invention and the manner and process of making and using it. It must enable the "person having ordinary skill in the art" to reproduce and use the invention without undue experimentation. A patent's claims are interpreted in light of the specification. that contradict this and the patentees’ amendment during prosecutionPatent prosecution is the process of applying for a patent, along with any further proceedings before the USPTO. to get around prior artPrior art is the knowledge in the field of a patent that was publicly available before the patent was filed. that had a platelet layer, but not a 100% platelet layer.

According to the Federal CircuitSee CAFC, reading a limitation from the specificationThe section of a patent that provides a description of the invention and the manner and process of making and using it. It must enable the "person having ordinary skill in the art" to reproduce and use the invention without undue experimentation. A patent's claims are interpreted in light of the specification. into the claims is “one of the cardinal sins of patent law.” But here, the Federal CircuitSee CAFC did exactly that, taking a clear term—“100% by weight”—and reading in limits from the specificationThe section of a patent that provides a description of the invention and the manner and process of making and using it. It must enable the "person having ordinary skill in the art" to reproduce and use the invention without undue experimentation. A patent's claims are interpreted in light of the specification. to stretch the meaning out to mean only that it’s 100% of the platelet material and 0% carrier, but we can safely ignore things that are neither platelet material nor carrier.

So a layer which is composed of 80% platelets and 20% dispersant by weight? That, according to the Federal CircuitSee CAFC, meets a limitation which—on the patent’s face—says “100% by weight.”

CAFC to the Public: A Word Means “Just What I Choose It To Mean”

Patents are supposed to “give[] notice to the public of the limits of the patent monopoly.” People should be able to look at the claims and say “I can do this, but not this.” But if the meaning of a claim is unclear or ambiguous, the scope of the patent monopoly becomes unclear. And when the scope of the patent monopoly is unclear, it creates a “zone of uncertainty which enterprise and experimentation may enter only at the risk of infringement claims.” This is a serious enough problem when a claim term is simply unclear, creating infringement risks for companies that innovate in areas like software where unclear claims are particularly common.

How much worse will the problem be if a company can’t even be sure that “100%” means “100%”?