A few weeks back, I outlined some of the problems created when design patentAs distinct from a utility patent. A design patent protects only the ornamental design or appearance of an article of manufacture, but not its structural or functional features. An ‘article of manufacture’ is a broad term which may extend even to computer icons. Like utility patents, design patents must be nonobvious but this standard is harder to apply to designs. law is interpreted in negative ways. One particular issue? The negative incentives created if the article of manufacture to which icon patents are applied is the entire device.

When I wrote that post, these were still hypotheticals.

A sole juror is rehashing the rationale behind their decision. She says they determined that one patent design was the whole phone because you need the phone to see it and another patent covered parts of it including the internal circuitry.

— Dorothy M. Atkins (@doratki) May 24, 2018

They’re not hypothetical anymore.

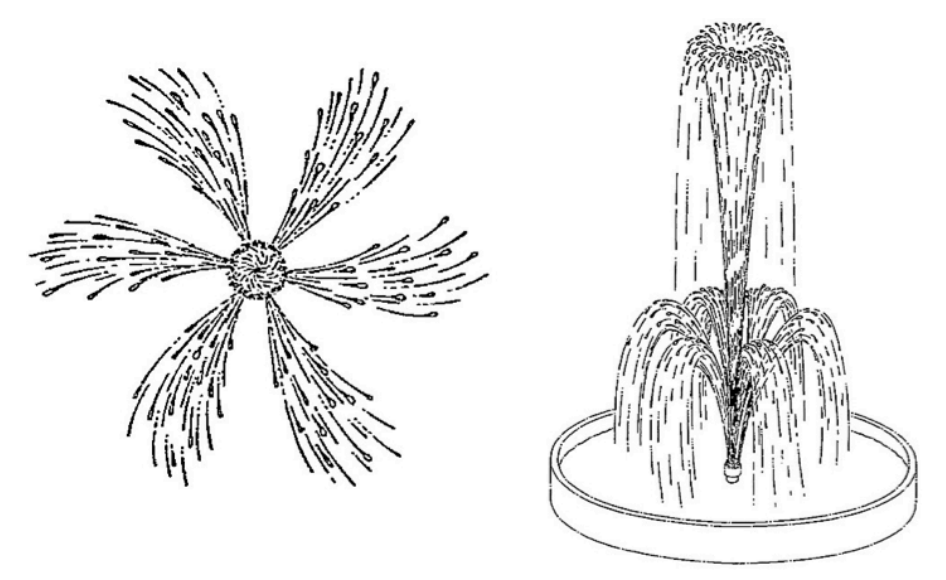

In re Hruby

That’s the practical problem. There’s also a simple legal problem—in re Hruby, the case that first allowed patents on ephemeral designs, made clear that an unclaimed device that produces a claimed design isn’t necessarily part of the article of manufacture, even though it might be required to reproduce the design.

Here’s what Hruby claimed as patentableEligible to be patented. To be patent-eligible, an invention must fall into the categories listed in 35 U.S.C. § 101 (i.e., process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter) and cannot be an abstract idea or a law of nature.:

The applicant himself made clear that the design patentAs distinct from a utility patent. A design patent protects only the ornamental design or appearance of an article of manufacture, but not its structural or functional features. An ‘article of manufacture’ is a broad term which may extend even to computer icons. Like utility patents, design patents must be nonobvious but this standard is harder to apply to designs. did not include a mechanical nozzle or similar components, only the water. Judge Rich clearly agreed, saying that “[t]he ‘goods’ in this instance are fountains, so they are made of the only substance fountains can be made of — water.” [1. We also know that the water itself was the entire article of manufacture because at the time Hruby was decided, patents on partial designs were not yet considered allowable, and the nozzle wasn’t depicted. Partial designs weren’t approved of until almost 15 years later, in in re Zahn.]

If the pumps and nozzles required to create a water fountain aren’t part of the article of manufacture, why are the various bits of silicon part of the article of manufacture simply because they might be used to create an icon grid?

Flawed Logic

The logic of the jury’s verdict also requires a different result than profits on the entire device.

Even if we assume, contrary to both good policy and established case law, that profits on the components that produce the icon grid are available, those components still aren’t the whole phone. The cellular hardware, for example, is not involved in producing a display (after all, Apple’s iPod Touch produced a similar display without any cellular functionality), but is still part of Samsung’s total costs and profits. For that matter, the external casing isn’t required in order to produce the grid of icons.

If the article of manufacture is defined by the hardware required to produce the icon grid, then it’s also defined as something other than the entire phone.

Flawed Results

It all comes back to a single problem. The design patentAs distinct from a utility patent. A design patent protects only the ornamental design or appearance of an article of manufacture, but not its structural or functional features. An ‘article of manufacture’ is a broad term which may extend even to computer icons. Like utility patents, design patents must be nonobvious but this standard is harder to apply to designs. total profits rule produces tests that are incoherent and impossible to apply when design patents are available for small pieces of complex, multi-component products. The total profits rule of § 289 simply doesn’t make sense in these situations.

This doesn’t mean that there’s no remedy. The damages available for utilityAn invention must useful to be patentable. Very few inventions are invalidated as lacking utility. Perpetual motion machines, for example, are typically found invalid for lacking utility. patents would remain available for design patents.[2. If § 284 had been in place at the time of the Dobson carpet case that led to the design patentAs distinct from a utility patent. A design patent protects only the ornamental design or appearance of an article of manufacture, but not its structural or functional features. An ‘article of manufacture’ is a broad term which may extend even to computer icons. Like utility patents, design patents must be nonobvious but this standard is harder to apply to designs. total profits rule, § 289 never would have emerged—the patent owner would have received at minimum a reasonable royalty, far more than the nominal damages awarded in Dobson.]

It just means that the concerns the total profits rule creates—concerns for industries ranging from automotive to startup technology to consumer goods makers—would be eliminated.