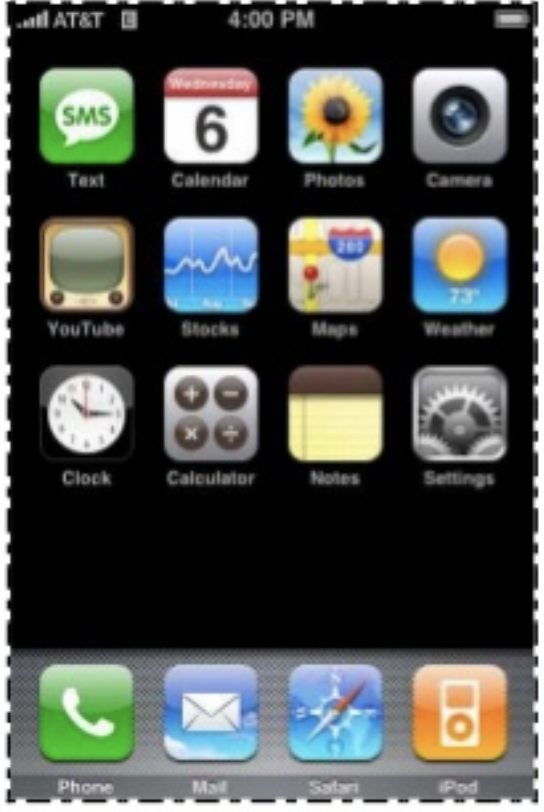

An important part of the Apple v. Samsung trial is about the exterior casing design patents. But those aren’t the only design patents at issue—the other design patentAs distinct from a utility patent. A design patent protects only the ornamental design or appearance of an article of manufacture, but not its structural or functional features. An ‘article of manufacture’ is a broad term which may extend even to computer icons. Like utility patents, design patents must be nonobvious but this standard is harder to apply to designs. in the case covers a colorful grid of icons with particular characteristics like rounded corners and variable icons:

As a reminder, a design patentAs distinct from a utility patent. A design patent protects only the ornamental design or appearance of an article of manufacture, but not its structural or functional features. An ‘article of manufacture’ is a broad term which may extend even to computer icons. Like utility patents, design patents must be nonobvious but this standard is harder to apply to designs. covers a “new, original and ornamental design for an article of manufacture.” Because an icon, standing alone, is treated as ‘mere surface ornamentation’, icon and GUI design patents are claimed as the icon or GUI (the ornamental design) as applied to a computer screen or other display.

Apple thus argues that Samsung’s infringing icon grid (again, infringement isn’t at issue in this trial, only damages) entitles them to the profits on the device that displays the interface—the entire phone.

Do We Kare?

Today, Apple will call Dr. Susan Kare as an expert in design. Dr. Kare has created some iconic designs, ranging from many of the typefaces and icons used in early Mac system software to icons in Windows 3.0 (many of which weren’t changed until Windows XP.)

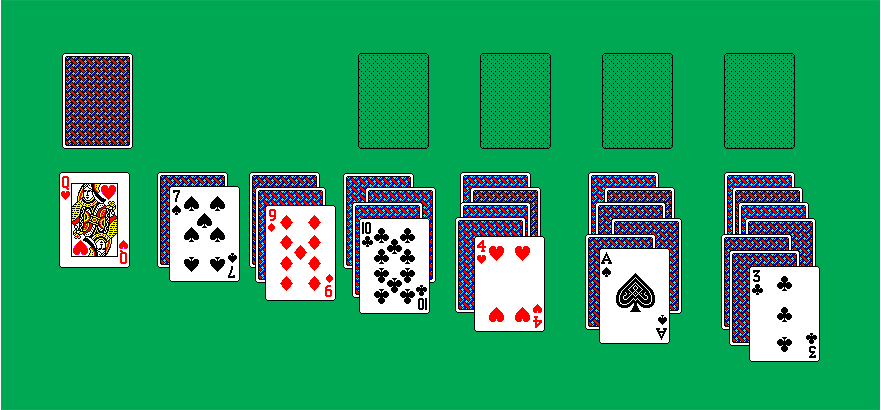

Dr. Kare also created the solitaire card deck used in Windows 3.0 Solitaire. I certainly spent my share of time staring at a screen much like this one:

While well-designed, I didn’t buy my copy of Windows because it had pretty cards in the Solitaire app.

But let’s imagine that someone out there had a design patentAs distinct from a utility patent. A design patent protects only the ornamental design or appearance of an article of manufacture, but not its structural or functional features. An ‘article of manufacture’ is a broad term which may extend even to computer icons. Like utility patents, design patents must be nonobvious but this standard is harder to apply to designs. for a computer icon representing a card back with the RGB pattern Dr. Kare used. Let’s imagine that a jury determined that her card back infringed that design patentAs distinct from a utility patent. A design patent protects only the ornamental design or appearance of an article of manufacture, but not its structural or functional features. An ‘article of manufacture’ is a broad term which may extend even to computer icons. Like utility patents, design patents must be nonobvious but this standard is harder to apply to designs..

What would the damages be?

Cards and Computers

Under Apple’s theory, where interface elements can force an infringer to disgorge the entire profits on the entire device, the infringing card backs could actually result in an award of damages on the entire computer. So that free solitaire game could force a manufacturer to give up their profits on the entire $1,000+ device.

At that point, the only cards computer manufacturers would sell would be the hardware ones.[1. For those of you who didn’t spend your youth taking apart and putting together computers, ‘cards’ can also refer to hardware circuit boards that are inserted into the main board of the computer to provide additional capabilities, such as graphics, expanded interfaces like USB or Firewire, Ethernet, Wi-Fi, and other capabilities.]

Deal Me Out

Much like with personal computers before, one of the major reasons for the success of modern smartphones is the possibility for anyone, anywhere, to write and release an app that runs on the phone. And the manufacturers try their hardest to get developers to write apps for their system, help them write apps, tell their users how to get new apps, and advertise based on the apps they have available.

For example, Apple regularly features third-party apps, suggesting that their users acquire and run that app. Now, imagine that one of those featured apps includes an infringing icon or GUI design. Say, an infringing card back in a featured card game.

The patent owner might well sue Apple for inducing infringement. Under the Power Integrations decision, that isn’t going to be an easy case to win—the patentee would need to prove Apple knew the app included an infringing design. But with the profits on the entire iPhone potentially at risk—after all, Apple is spending this week arguing that an icon interface gives rise to the total profits on the device it runs on—would Apple take the chance of losing?

Or would the open app ecosystem that smartphone users benefit from suddenly close up, with smartphone OS makers unwilling to showcase third-party apps? Would they go further and strictly limit who can release apps, rather than risk their profits on every single phone they sell?

Screening Out Risk

Again—these wouldn’t necessarily be easy cases for the patent owner to win. But the potential risk of each case would be immense. Incentives to mitigate that risk by reducing exposure to design lawsuits, and to settle lawsuits even if their merits are weak, would be immense.

And imagine the impact on new products currently being designed. IoT and smart home devices are a huge area of growth. Increasingly, smart home devices include a screen. If you’re designing a new smart home product, are you going to provide third parties with the ability to display icons on the screen if there’s a potential that it will result in you being liable for the total profits on the device?

Revisiting § 289

The design patentAs distinct from a utility patent. A design patent protects only the ornamental design or appearance of an article of manufacture, but not its structural or functional features. An ‘article of manufacture’ is a broad term which may extend even to computer icons. Like utility patents, design patents must be nonobvious but this standard is harder to apply to designs. total profits rule of § 289 was created in an era when awards of profits were common and where complex multi-component products like we have today were uncommon. (Obviously, the concept of a computing device with an ecosystem of third-party app developers wasn’t even within the realm of imagination when § 289 was written.)

In fact, § 289 was created as a reaction to a decision about carpet decorations. A customer might seek out and buy a carpet just because of the design. But for most products today, that simply isn’t the case.

In order to avoid the kind of perverse results I’ve described, the article of manufacture for an icon or GUI should be interpreted as the software, not the device it runs on. And even if that change were made, Congress should still consider revisiting the total profits rule. A single infringing icon that’s a small part of a complex operating system shouldn’t entitle a patent owner to the total profits on the whole operating system—no matter how iconic it might be.