You might be familiar with Bob Sachs’ term “Alice Storm.” Sachs and his co-authors over at Bilski Blog argue that “Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank has had a dramatic impact on the allowability of computer implemented inventions.”

I disagree, and some newly released data from the Patent Office seems to back me up. Alice has had a limited impact overall, and much of that impact is centered on patent applications that were drafted before Alice (and her Federal CircuitSee CAFC children, like DDR Holdings and McRO) was decided. For the “Alice Storm”, you don’t even need an umbrella.

PTOPatent and Trademark Office, informally used interchangeably with USPTO. Data At The Office Action Level

The Patent Office recently released an incredibly useful set of data. Combining their internal text-formatted office action documents with machine learning techniques, the PTOPatent and Trademark Office, informally used interchangeably with USPTO. mined through the last decade of office actions and classified them according to whether a given office action included a rejection under § 101 for patentableEligible to be patented. To be patent-eligible, an invention must fall into the categories listed in 35 U.S.C. § 101 (i.e., process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter) and cannot be an abstract idea or a law of nature. subject matter, a rejection under § 102 for noveltyA requirement for patentability, based on 35 U.S.C. § 102(a) of the Patent Act. An invention cannot have been disclosed, offered for sale, or used publicly more than a year before seeking a patent., § 103 for non-obviousnessA requirement for patentability based on 35 U.S.C. § 103 of the Patent Act. An invention cannot be an obvious variant of something that is already known, that is, the invention must not be obvious to a "person having ordinary skill in the art" (PHOSITA). Also known as an "inventive step" outside the United States., § 112 for written description, definiteness, or enablement, and whether a double patenting rejection was included. (For full details on how they did all this, you can read their white paper.)

I recently wrote about Google’s Patents Public Data dataset for use with BigQuery. After the Patent Office released their office action data, Google swiftly included the data in BigQuery. Which means that I can look at the impact by doing something as simple as:

[expand title=”SQL Query for Percentage Rejections By Year And Type“]

#standardSQLSELECT yr, SUM(r101) / COUNT(*) AS p101, SUM(r102) / COUNT(*) AS p102, SUM(r103) / COUNT(*) AS p103, SUM(r112) / COUNT(*) AS p112, SUM(dp) / COUNT(*) AS pdpFROM (SELECTSPLIT(mail_dt, "-")[SAFE_ORDINAL(1)] AS yr,IF(rejection_101 = "1", 1, 0) r101,IF(rejection_102 = "1", 1, 0) r102,IF(rejection_103 = "1", 1, 0) r103,IF(rejection_112 = "1", 1, 0) r112,IF(rejection_dp = "1", 1, 0) dpFROM `patents-public-data.uspto_oce_office_actions.office_actions` oa)GROUP BY yrORDER BY yr ASC;

[/expand]

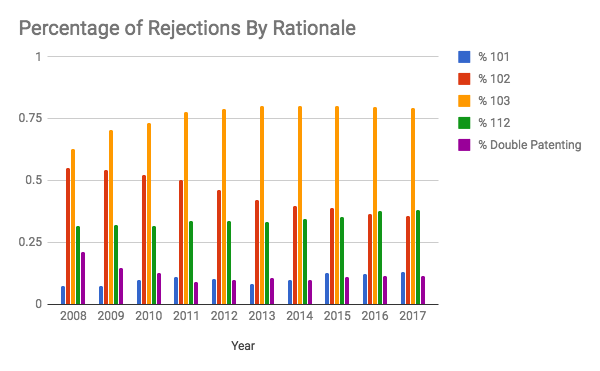

That query looks through all of the office actions in the PTO’s data set and gives me the percentage, by year, of each type of rejection.

Looking Year-By-Year At Rejections

If we take a look at this, keeping in mind certain key years (2010 for Bilski, 2012 for Mayo, 2013 for Myriad, and 2014 for Alice and Nautilus), we should be able to draw some conclusions about the impacts of those cases.

The result? (Because a single office action may include more than one type of rejection, these numbers will not sum to 100%.)

It turns out that the impacts of these cases just aren’t that large in the grand scheme.[1. One case that might have had a bigger impact, but is just a little too early to entirely appear in this data, is 2007’s KSR case. The approximately 15% increase in rejections under § 103 and similar decrease in § 102 rejections could be due to KSR’s rejection of the Federal Circuit’s rigid obviousness test in favor of a more flexible obviousness test that examiners can apply in common sense ways.] After Bilski, rejections under § 101 went up slightly, then went back down over the next few years. Mayo and Myriad don’t seem to have significantly affected the number of § 101 rejections. And then we get to the alleged master villain, Alice. The end result of Alice?

Of the approximately 2.15 million office actions issued after Alice was handed down, there were around 65,000 more office actions including § 101 rejections than there would have been pre-Alice. And that’s office actions, not patent applications—a given patent application likely saw more than one office action in that time frame, so even fewer patent applications would have been affected.

For comparison, we can look at the impact of Nautilus, another 2014 case, on § 112. The increase in § 112 rejections post-Nautilus is approximately as large as the increase in § 101 rejections post-Alice. For some reason, no one is talking about the “Nautilus maelstrom.”

Drawing Lessons

One lesson that we can draw from this is that Alice clearly didn’t ‘dramatically impact the allowance of computer-implemented inventions.’ Instead, Alice provides the Patent Office and courts with a useful and appropriate tool for dealing with low-quality patents on abstract ideas—patents that shouldn’t be allowed in the first place—but most computer-implemented inventions aren’t that kind of patent.

A second lesson is that, if we look at the post-Bilski rate of § 101 rejections, we see an initial spike followed by a decline. Patents that were written pre-Bilski were rejected more frequently, but as the Bilski case law developed, patent attorneys drafted patents to comply with Bilski and the rate went back down. In my experience, the same is true after Alice. Applications drafted prior to Alice weren’t drafted in ways that could overcome § 101 rejections; patents drafted after Alice are far more likely to do so. A quick look at the data in BigQuery suggests my intuition is correct—office actions on patents drafted pre-Alice appear significantly more likely to include a § 101 rejection than those drafted post-Alice.

While Alice’s § 101 impact is limited, it is worth looking at how applications that receive § 101 rejections fare. In a future post, I’ll take a look at the impact of Alice on applications that receive rejections under § 101—are they abandoned, and if so, why? How many of those abandonments are due to the § 101 rejection? And how many patents ultimately issue, overcoming § 101?