Tomorrow morning, the House Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property, and the Internet is holding a hearing on “The Impact of Bad Patents on American Businesses.”

The impact of bad patents is a topic worth taking some time to examine, because it isn’t just about the direct impact from abusive trollAn entity in the business of being infringed — by analogy to the mythological troll that exacted payments from the unwary. Cf. NPE, PAE, PME. See Reitzig and Henkel, Patent Trolls, the Sustainability of ‘Locking-in-to-Extort’ Strategies, and Implications for Innovating Firms. litigation—bad patents cause a lot of harm even if they’re never asserted.

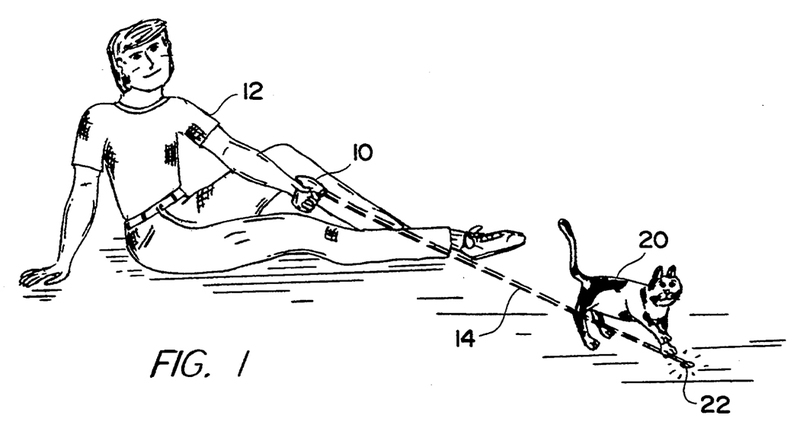

I’m going to start out with a definition. There are good patents out there. They’re not what we’re talking about. We’re talking about “bad patents.” You know. These:

And while exercising a cat is an extreme example, bad patents include more than just the ridiculous patents.

What’s a “bad patent”? It’s a patent that’s on an abstract building block of technology, or is on an idea that isn’t actually new or is just a trivial variation that any engineer could have come up with. It’s a patent that’s so poorly written that it’s impossible to understand what it covers. These kinds of patents are “bad patents”—the patents that should never have been issued in the first place.

And they cost businesses (and consumers) a lot of money.

Money—It’s A Hit (To The Bottom Line)

The most infamous impact of non-practicing entity (NPENon-Practicing Entity. A broad term associated with trolls but now disfavored because it includes universities and legitimate technology developers that seek to license technology in advance rather than after a producing company has independently developed it. More) litigation is the direct economic costs that are front and center. Those costs have been estimated to be in the range of $30 billion a year, if not more. (And the study I linked notes that the amount has increased in recent years, reflecting the increase in litigation.)

And it’s not just damages! The costs include litigation costs as well. According to an AIPLAAmerican Intellectual Property Law Association, formerly the American Patent Law Association. DC-based professional organization that represents the interests of the intellectual property community, including the patent bar. survey, the median cost of a single litigation (including attorneys, experts, support teams, document production and review, etc.) ranges from $600k up to $5m, depending on how much money is at stake. That’s the median amount—it can go a healthy way into the eight figure range in some cases.

But beyond the direct economic costs from litigation, there are other real costs to companies.

Stop—Lawyer Time!

For one thing, to defend against patent litigation, you’re going to need to take your engineers away from doing actual engineering work and force them to talk to lawyers.

In my experience, engineers are usually not happy about having to talk to lawyers. I’ve never understood why.

And then, as it gets closer to trial, you’re going to need to prepare the engineers for deposition, depose them, and eventually present them at trial. By the time the case ends, you might lose a week or two of their time. Taking productive time away from an engineer is a significant indirect cost to a company, and one that economic studies of the costs of patent litigation typically don’t model.

Can I Do That? Should I?

You also might, depending on your industry, decide it’s worth doing what’s called a “freedom-to-operate” analysis. If there are hundreds of thousands of relevant patents, like for a smartphone, you can’t really do this. But in some industries, it’s possible to have lawyers take a look at your competitor’s patents and figure out if your products infringe and if their patents are valid. The lawyers might also take even more time away from your engineers to try to redesign your product in a non-infringing way, a process called “designing around” a patent.

While freedom-to-operate is cheaper than litigation (which is why some companies do it), it’s still not cheap. An opinion might cost you $25k-$50k dollars per patent. If you have to cover 10 or 12 patents to feel reasonably safe that your product won’t get sued, that’s a significant amount of money for each product you launch.

I’d Rather Not Do That, Actually

And of course, there’s the other option. Just… don’t. Whatever it is that might get you sued, just don’t do it.

Smartphones are heavily patented, and lawsuits are common. Is it worth trying to create the next iPhone? If you know you’re going to get hit with a patent lawsuit (or 20) in the process, maybe it isn’t. And even if it’s still worth trying to launch a product, you’re probably going to need to budget in increased legal costs, which means you’re going to charge more for the product. That makes your product less competitive, and raises the price consumers pay for it.

And if your core business is, say, selling delicious hamburgers or just selling things in general, then maybe it isn’t worth putting that business at risk by texting out coupons if that might get you sued. Or, if you still want to do it, you might only be willing to buy the technology from a large company, rather than a startup, because the large company can defend you, but the startup can’t afford to.

Bad patents lead to fewer products being developed and make it harder for small businesses to succeed.

How Do Bad Patents Make This Worse?

The simple answer is that, if the patents we were talking about were new ideas that covered something non-obvious, then the costs I just talked about would be the cost of obtaining those new ideas. We’d be getting something for our trouble—we’d be “promot[ing] the Progress of Science and useful Arts.”

But when the patents are on abstract ideas, old ideas, obvious ideas, or are just plain incoherent, we haven’t promoted progress. All we’ve done is create legal instruments that cause all of the costs with none of the innovation. That’s part of why bad patents are a problem—we get all the negatives with none of the positives.

But it gets worse. All of these problems are exacerbated when you have bad patents. A patent that has vague and broad claims means that it’s that much harder to understand whether your business is at risk. And a patent that claims old ideas might be invalid, but you’re going to have to spend anywhere from $300,000 to $10,000,000+ to prove that the patent’s invalid. That’s a lot of money to spend when you can do something else instead. The uncertainty of whether the patent targets you, and the cost to show that it isn’t valid, combine to make the impact of a bad patent worse.

It doesn’t even matter if the patent is asserted. The fact that bad patents exist can be enough to inflict harm on companies and consumers.

Patent Owners Suffer Too

This isn’t just a problem for defendants in patent litigation, either. Bad patents impact patent owners. It costs money to obtain a patent, and more money to investigate and attempt to assert that patent. When a patent owner spends that money and receives a bad patent, that money might wind up being a total waste when their patent is (rightfully) determined to be invalid.

But the solution to that problem is to prevent invalid patents from being issued, not to make it harder to invalidate bad patents. That’s why I’ve criticized the SPA—it does exactly the opposite of what we need to do in order to give patent owners certainty that their investments aren’t wasted. And it’s probably why, when a room full of patent attorneys and intellectual property counsel from companies was asked their thoughts on SPA at the USPTO’s PTABPatent Trial and Appeal Board. Reviews adverse decisions of examiners on written appeals of applicants and appeals of reexaminations, and conducts inter partes reviews and post-grant reviews. The Board also continues to decide patent interferences, as it was known as the Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences (BPAI) before the AIA. Judicial Conference last month, there was essentially zero support. That room was full of people who understand the value of the patent system, and none of them felt that SPA was a good idea.

What Can We Do?

There’s some good empirical research out there on how the Patent Office operates and how we can improve that. Professor Michael Frakes and Professor Melissa Wasserman have done a lot of it, examining how Patent Office procedures impact examiners’ ability to issue good patents and reject bad ones. ([1] [2] [3] [4].) If we’re trying to eliminate bad patents to limit their impact, we could do a lot worse than starting with Frakes and Wasserman’s proposals: give examiners (particularly more senior examiners) more time for review, and eliminate the Patent Office’s use of post-allowance fees to subsidize examination costs.