Tuesday, Kaldren LLC sued Snap. (According to RPX, Kaldren is affiliated with IP Edge, a notorious patent trollAn entity in the business of being infringed — by analogy to the mythological troll that exacted payments from the unwary. Cf. NPE, PAE, PME. See Reitzig and Henkel, Patent Trolls, the Sustainability of ‘Locking-in-to-Extort’ Strategies, and Implications for Innovating Firms..) Kaldren sued over a set of expired patents on such wonderful ideas as:

- Printing out a machine readable symbol;

- Reading a machine readable symbol;

- Using an address in a machine readable symbol to retrieve information from that address; and

- Communicating with an address contained in a machine readable symbol.

That’s not one patent for all four things done together. That’s four different patents, one for each of those ideas. And all of those ideas seem kind of familiar to me.

Just as one example:

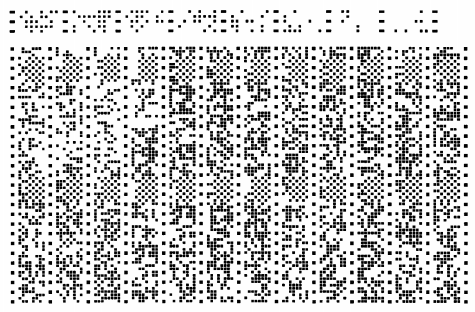

And if you look closely at some of your mail, you’ll see something that looks like this:

![]()

So, yeah. Kaldren is trying to exert ownership over the idea of a bar code.

Out Of The Frying Pan, Into The Kaldren

Now, Snapchat doesn’t use the kind of barcodes you might see on a cereal box or a book. They do, however, use something similar to a barcode — their Snapcodes. Here’s a Snapcode:

The pattern of the dots (just like the pattern of lines in a barcode, or the pattern of squares in a QR code) encodes information—in this case, the URL for Patent Progress.

That’s it. That’s what Kaldren claims to own. Encoding information into a set of dots, reading that information, and using it in communications and messaging.

The PTOPatent and Trademark Office, informally used interchangeably with USPTO. Calling The Kaldren Abstract

Kaldren is claiming their patents cover incredibly broad abstract concepts about how you can put digital data on paper and use that representation. That’s an abstract ideaAbstract ideas are not patent-eligible subject matter. This judicially developed exclusion was most recently explained by the Supreme Court in Bilski v. Kappos, 2010. More under § 101—it’s exactly what § 101 is intended to prevent. Patents aren’t supposed to cover all ways of doing something, they’re supposed to cover specific implementations. Here’s what one of the Kaldren patents claims:

defining at least one attribute of said at least one symbol in terms of printer pixels; and

formatting said at least one symbol into said pattern.

You can’t just claim “formatting a symbol for printing.” You have to provide a specific solution. And that’s exactly what Kaldren’s patents fail to do.

An Old, Old Kaldren

Kaldren is claiming their patents cover Snapcodes. Let’s give them the benefit of the doubt and say that they aren’t claiming to own the kind of barcodes we all know extremely well, they just own two-dimensional data codes.

The problem is, the idea of storing data in a two-dimensional code existed before they filed for a patent. I’ve placed two images below. One is from Kaldren’s patents. One is from a Pitney-Bowes patent from back in the 1980s.

Which one is which?

Both store data in a set of dots. This idea of storing data in a set of dots? It isn’t new. And the postal mail example above shows that it isn’t any less obvious to use those codes to store an address and then send a communication to that address, whatever Kaldren may claim in this case.

When a patent is asserted which isn’t actually new, and isn’t non-obvious, that’s when an inter partes review (IPRIntellectual Property Rights. Usually associated with formal legal rights such as patent, trademark, and copyright. Intellectual property is a broader term that encompasses knowledge, information, and data considered proprietary whether or not it is formally protected.) is appropriate. An IPRIntellectual Property Rights. Usually associated with formal legal rights such as patent, trademark, and copyright. Intellectual property is a broader term that encompasses knowledge, information, and data considered proprietary whether or not it is formally protected. gives the Patent Office a chance to look at the patent and to look at the prior artPrior art is the knowledge in the field of a patent that was publicly available before the patent was filed. and decide whether the patent should have been granted in the first place.

This Is Why We Need § 101 And IPRs

Patent Progress has written about how businesses use Alice and § 101 to stop patent trolls. And we’ve talked about the inter partes review process and how that can be used as well.

The Kaldren v. Snap case has all the hallmarks of a case that shows why both § 101 and IPRs are good for the patent system. Without § 101 or IPRs, they’d face a long and expensive lawsuit in order to have an opportunity to convince a jury that the Kaldren patents are about old technology and should never have issued. With § 101 and IPRs, they at least have an opportunity to show the court early on that the patents are about abstract ideas, and an opportunity to go to the Patent Office and ask that they take a second, more detailed look at whether these patents should have issued in the first place.