AIPLAAmerican Intellectual Property Law Association, formerly the American Patent Law Association. DC-based professional organization that represents the interests of the intellectual property community, including the patent bar., the bar association for intellectual property lawyers, just released their recommendation and report on reforming § 101. § 101 is the portion of the Patent Act that sets out what’s eligible to be patented, and what isn’t. AIPLA’s basic complaint is that the Supreme Court has created uncertainty about what is eligible for patenting — they claim their proposal will provide certainty again.

The AIPLAAmerican Intellectual Property Law Association, formerly the American Patent Law Association. DC-based professional organization that represents the interests of the intellectual property community, including the patent bar. proposal is essentially identical to the Intellectual Property Owners Association (IPOIntellectual Property Owners Association, an association that represents the patent interests of major companies.)’s January proposal, which Patent Progress covered back in February. As Matt Levy said, “this is a solution in search of a problem.” Both proposals serve one set of interests: the interests of patent owners. Everyone else isn’t going to find much to like here.

AIPLA’s main goal is to eliminate any real constraint on subject matter eligibility. While they claim § 101 “is not meant to provide the standard for deciding whether a particular technical advance should receive patent protection,” a series of Supreme Court cases have outlined why § 101 does exactly that. More importantly, the Court explains that § 101 has to, because it protects access to “the basic tools of scientific and technological work.”

AIPLA’s proposal does not.

Patent All The Things

AIPLAAmerican Intellectual Property Law Association, formerly the American Patent Law Association. DC-based professional organization that represents the interests of the intellectual property community, including the patent bar. envisions essentially everything as being patentableEligible to be patented. To be patent-eligible, an invention must fall into the categories listed in 35 U.S.C. § 101 (i.e., process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter) and cannot be an abstract idea or a law of nature., so long as it doesn’t exist in nature independent of humans and can’t be performed solely in the human mind. But if you add a computer, or even a pencil and paper, it’s suddenly patentableEligible to be patented. To be patent-eligible, an invention must fall into the categories listed in 35 U.S.C. § 101 (i.e., process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter) and cannot be an abstract idea or a law of nature..

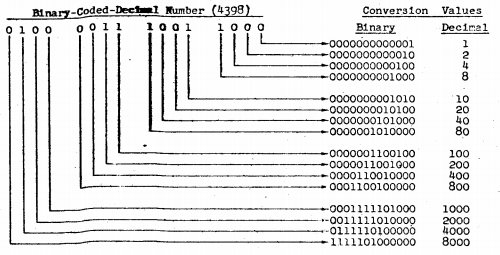

So a patent on translating from binary digits to decimal digits? PatentableEligible to be patented. To be patent-eligible, an invention must fall into the categories listed in 35 U.S.C. § 101 (i.e., process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter) and cannot be an abstract idea or a law of nature., as long as it’s computer-implemented (even though such a patent was rejected in Gottschalk and would have set back the development of computer technology by decades.)

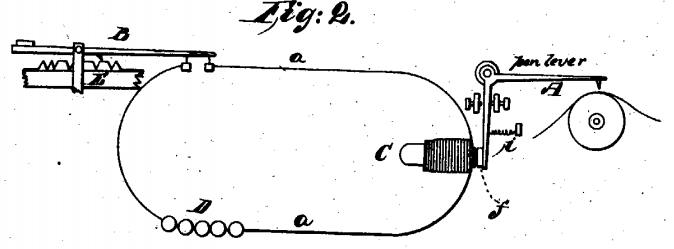

A patent on using electromagnetism to transmit characters over a distance? PatentableEligible to be patented. To be patent-eligible, an invention must fall into the categories listed in 35 U.S.C. § 101 (i.e., process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter) and cannot be an abstract idea or a law of nature. (even though Morse rejected it.) AIPLAAmerican Intellectual Property Law Association, formerly the American Patent Law Association. DC-based professional organization that represents the interests of the intellectual property community, including the patent bar. rejects the basic cases that have guided subject-matter eligibility since the beginning of patent law.

Some Obvious Problems

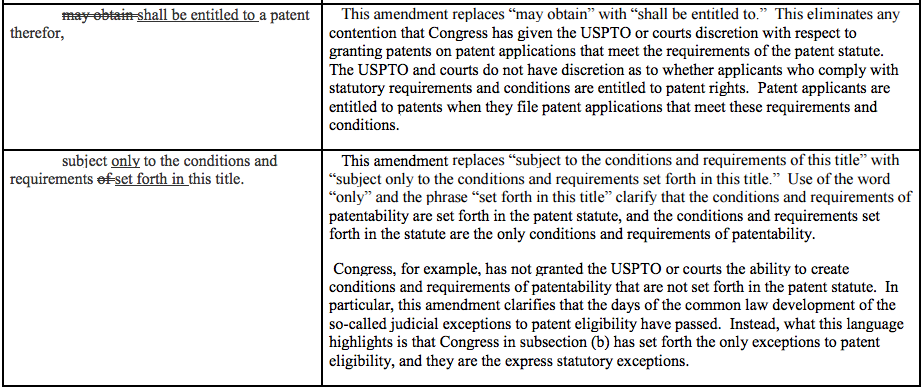

The AIPLAAmerican Intellectual Property Law Association, formerly the American Patent Law Association. DC-based professional organization that represents the interests of the intellectual property community, including the patent bar. proposal also changes “may obtain a patent subject to the conditions and requirements of this title” to “shall be entitled to a patent only subject to the conditions and requirements set forth in this title.” While this may sound like a small change, AIPLAAmerican Intellectual Property Law Association, formerly the American Patent Law Association. DC-based professional organization that represents the interests of the intellectual property community, including the patent bar. itself admits that it’s intended to eliminate any discretion the PTOPatent and Trademark Office, informally used interchangeably with USPTO. or courts might have.

AIPLAAmerican Intellectual Property Law Association, formerly the American Patent Law Association. DC-based professional organization that represents the interests of the intellectual property community, including the patent bar. tries to call this an improvement, saying “the days of the common law development of the so-called judicial exceptions to patent eligibility have passed.”

What they don’t say is that this change could eliminate the existing exceptions as well. There are a number of these, including so-called “obviousness-type double patenting.” This rule was created to prevent patentees from obtaining extensions of their patent monopoly. Essentially, if a patent application has claims that are an obvious variation of another application (or patent) by the same inventor, then obviousness-type double patenting requires them to file a “terminal disclaimer,” which limits the lifespan of the new patent and prevents it from being transferred independent of the old patent.

The point of the rule against obviousness-type double patenting is simple — patent owners shouldn’t be able to get trivial variations of their patent and extend their term by doing so. The patent bargain is exclusivity for a limited time. But the statute itself doesn’t set the rule against obviousness-type double patenting; courts created this doctrine for public benefit (backstopped by § 101.) And because the statute itself doesn’t set the rule against obvious variations by a patent owner, the AIPLAAmerican Intellectual Property Law Association, formerly the American Patent Law Association. DC-based professional organization that represents the interests of the intellectual property community, including the patent bar. amendment appears to eliminate it.

What does that really mean? It means that, among other things, companies would have a new avenue to evergreen their patents. File within a year of original filing, or even later if the original application hasn’t published yet, and you can get a year, or even more, of term extension. In some cases (such as pharmaceuticals), that extra year of exclusivity might be worth billions of dollars.

AIPLAAmerican Intellectual Property Law Association, formerly the American Patent Law Association. DC-based professional organization that represents the interests of the intellectual property community, including the patent bar. drafted this amendment to provide certainty, and it will. Adopting this will certainly result in the issuance of patents that never should have granted.